Loving Conflict v. Loving Conflict

We can have a bias towards “keeping the peace” at all costs, even when it’s harmful to ourselves or others. But conflict can be healthy, especially when it’s engaged in lovingly.

A friend recently told me that she was worried about her new romantic relationship because she and her partner had yet to really “butt-heads” and “get into it.” Although, in her case, I didn’t think she had anything to worry about, her concern nevertheless struck me as appropriate and sane. Some part of us intuitively understands that conflict is a healthy part of any long-term relationship, whether it be with a romantic partner, a friend, a family member, a spiritual community, or one’s fellow citizens. When we’re skillful, conflict can deepen a relationship and demonstrate a certain willingness to invest in one another’s well-being. And don’t we all want people to invest in our well-being?

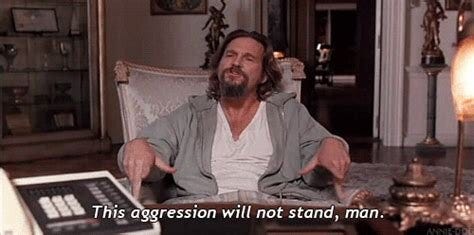

At the same time, just because conflict is a healthy part of relational life doesn’t mean we have to go out, fists up, looking for a fight. But, it does mean that we should be wary of sacrificing the rewards of speaking our truth in order to dodge discomfort or maintain some appearance of peace. Ah, if it were only easy to speak our truth! Indeed, if this is challenging for you, you’re in good company. Despite having been a litigator, I’m pretty averse to interpersonal tension. This is something I’m working on because, my bias of “keeping the peace at all costs” is actually one that repeatedly ends up attenuating compassion and intimacy rather than fostering it. As we’ll see, conflict avoidance can also compromise the success of liberation movements, whose efforts are critical to assuring that marginalized persons are free to be. So, in this post, I am thinking “out-loud” and exploring how we actually engage in healthy conflict without being… well… jerks! How do we affirm the belonging of all peoples while also putting our foot down when enough is enough? How do we say what’s true for us in the moment, while also being open to changing our minds? What’s the distinction between engaging conflict lovingly and being a conflict-lover, aggressively combating others for ego’s sake?

Before we get into it, I feel the need to emphasize the importance of this question. As I eluded to above, not only is healthy conflict essential on the interpersonal plane (to deepen personal relationships), it is also essential for justice and social transformation. We have an apathy problem in the United States: many of us believe ourselves to be somehow neutral or outside the problems of racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, Islamophobia, ableism, ageism, and anti-immigration sentiments. But, no one is outside the system in which these collective dysfunctions arise, and refusing to engage these realities and failing to integrate them within the scope of our awareness is just as much a political stance as anything else. An unethical one at that.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. often lamented this false peace that comes from not risking conflict. For King, true peace is not the “absence of tension,” but is instead “the presence of justice.” In his 1963 Letter from the Birmingham Jail, King expressed his anger and frustration with folks who claimed to be empathetic to his cause, but who stood on the sidelines to maintain their own comfort and some skewed semblance of social “order.” He wrote,

“Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

As Robin DiAngelo notes in her recently published book Nice Racism,

“King speaks to the tendency of white moderates to see a lack of struggle as an indicator of racial justice. He notes that no racial progress has ever been made without conflict” (pg. 3).

Surely, we should take Dr. King’s prophetic comments to heart and consider how conflict is necessary to disrupt the false peace that, ultimately, serves to maintain systems of oppression. So, whether we avoid conflict to make our next Thanksgiving less tense (but just as painful), or whether we avoid it to secure our own comfort in the face of collective realities that are deeply disturbing, I invite us to explore what circumstances make disagreement and disruption worthy endeavors. If we trust Kingian wisdom: conflict, when engaged in strategically and skillfully, can be used to generate a more authentic peace — a peace rooted in truth-telling, justice, and a willingness to repair harm and move forward.

Silence is Tricky

What was that old saying teachers and parents used to tell us as school kids? It was something like,“if you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all,” right? Ugh. Well my friends, the question (as always) is: who does this mantra serve? And who does it not serve? Silence gets tricky first and foremost when it either enables or condones abuse or unethical behavior. Sure, when we speak out against abuse or unethical behavior we can always endeavor to be diplomatic, but being overly concerned with “niceness” can detract from the one-pointedness needed to cut through to results. I’m guilty of this. I’m embarrassed to say, I’m often overly concerned with “appearing nice,” and no doubt this tendency comes from both misguided feminine conditioning (and my reification of that conditioning), as well as some insecure need to be liked. And so, too often, I circumambulate around a “nice” persona, and sometimes use silence in order to ensure I’m “in.”

But do I really want to forego telling friends and family that I’m hurting? And do I really want to belong to the side of history that enables harm and violence through my passivity? Habits of silence to “save face” or “smooth things over” when there has been real, palpable harm doesn’t lead to healing; nor does it lead to lasting, healthy relationships; nor does it lead to justice. In fact, it is precisely our silence bias that enables dysfunctional systems (whether familial, communal, or national) to continue reproducing harm. For example, part of the way white supremacy re-perpetuates itself is through the silence of so-called “moderate” and “progressive” whites. This silence continues despite Black, Brown, and Asian Americans being assaulted and murdered in the public eye, and despite chronic discrimination against people of color and indigenous folks when it comes to housing, healthcare, financial lending, education, voting rights, and job opportunities. Moreover, this isn’t only a domestic issue. Silence is deadly on the international stage as well. Consider what happened when places like Tibet and Palestine cried out for help: the world largely remained silent, allowing occupation, cultural destruction, and genocide to continue unabated. In this way, silence can literally be deadly, and can actively contribute to the demoralization and destruction of a whole people.

If we have trouble understanding how silence can be harmful on the collective scale, we can start by examining our own personal relationships. Because it’s certainly true — on the interpersonal plane as well — silence can enable a relational dynamic that is hurtful, and also harmful to our emotional and spiritual development. We’ve all had dynamics with friends, lovers, co-workers or family members that felt somehow imbalanced. In these imbalanced relationships, we repeatedly offer someone else the space to air their grievances, while we become exhausted (or even demoralized and disheartened.) I think it’s great to be there for others, but if we find ourselves continually depleted, perhaps it’s okay to speak up and say what we notice. We needn’t be unkind, but it’s okay to allow our eyes to widen and to show our upset. All this assumes, of course, that we want to work on this relationship with the hopes of keeping it. Otherwise, tip your hat to this person, acknowledge this is where they’re at, and move on.

So, silence can enable abuse, injustice, unethical behavior, and dysfunctional relationships. But, not only that. As Sarah Schulman points out in her book Conflict is Not Abuse, silence as a response to someone’s grievances can be a punitive act. It can be a cruel way to retaliate. This punitive kind of silence comes into play when someone has the guts to tell you that you are behaving in a way that is hurtful. It’s hard to hear when we’ve messed up. If we’re not careful, we can be tempted to lash out by using silence to punish the person who had the courage to bring up what was challenging for them. We fool ourselves into thinking we are “noble” for not “stoking the fire.” We say “whatever,” we walk away, we hang up the phone, we literally physically leave a person in their grief. That’s super challenging for the person who tried to teach us about the impacts of our behavior. No one wants to feel that kind of exasperating loneliness in their pain. So, even if we can’t respond totally open-heartedly in the moment, it might help to at least muster a simple, “I hear you, thanks for telling me this. I’m going to have to calm down and get back to you.”

There are two major caveats to this roast on silence. First, there’s definitely such a thing as healthy forbearance. Within liberation movements, within families, within friendships, within partnerships: people make mistakes. Healthy forbearance means we don’t “nail” a person every time they make one. We weigh the situation thoughtfully with tenderness and mercy, and see what would be most helpful. Sometimes that means forbearing confrontation. My partner Dave frequently shares with me his inner contemplation in moments like these. He ponders: “Does this need to be said? Does this need to be said right now? Does this need to be said by me?” I find it helpful. In situations where I am the only the woman of color talking to a group of resistant white men about racial injustice and patriarchy the answers are often “um…yes, yes, and hell yes!” But sometimes, when a friend or family member makes a passing slight on my character in a joking way, and I know they didn’t mean to hurt me, I feel what I feel and move on. It’s up to us to make this forbearance-or-conflict determination, and I think we can trust ourselves in doing so as long as we engage what’s happening with an open and compassionate heart.

Second, silence is sometimes downright necessary when we need space to self-regulate our coarse and subtle bodies. Everyone has a right to protect their body and self-regulate their nervous system. This is especially critical for those of us in oppressed minority groups: when we are traumatized by the very systems we are endeavoring to disrupt, and we need a minute, a week, a month, or however long to regroup, we are entitled to that. Assuring time for recovery and spaciousness is part of the work of disrupting violent systems. Silence may be needed for that, and if silence is needed: silence is needed! Without anyone’s permission. Yet for those of us in dominant groups: this doesn’t mean that discomfort and tension are tantamount to non-safety of the body. So be careful with claiming “I don’t feel safe and therefore need to be quiet,” when what you actually mean is that your ego just got royally bruised and you’re using silence to punish or disengage. That may actually be a healthy ego bruising, and simply part and parcel of becoming socially responsible. So, silence for taking care of yourself and protecting the body: yes, absolutely; silence as a ploy to avoid awkwardness: maybe hang-out in the messiness a little longer, you’re on the right track!

An Alternative Guiding Mantra: “We’re Not Aligned, But You Still Belong”

So, the whole “if-you-can’t-say-something-nice, don’t-say-anything-at-all-thing” is a bit of a bust. What then might guide us in navigating conflict? No doubt each of you could come up with helpful (and even poetic!) mantras, but I’ll just share the one I’m working with. It’s this: “we’re not aligned, but you still belong.” This is not so much something I explicitly say, as much as it is an ethos I endeavor to embody. Here’s how I think about it…

Let’s say, some shit has just gone down. Maybe someone has just said something hurtful, or is about to do something unethical, or you’re noticing a dysfunctional relational or systemic pattern play out. The first part of this mantra — “we’re not aligned” — invites us to notice that and speak up. We’ve determined that silence in this case would unnecessarily condone hurtful or unjust conduct, and so we choose to respond. We’re ready to state unequivocally what needs to be named. This might mean describing our needs, stating our disagreement, or otherwise differentiating ourselves from tacit adoption of what was just said or what is taking place. In short, “we’re not aligned” is the part of our conflict-guidance-mantra that gives us total permission to speak up when something or someone is threatening our right to be well, or the rights of others to be well.

But here, I must state an aside, my loves. Even as we face potential conflict, we benefit greatly from simultaneous internal work. Because here’s the deal: we want to be able to respond, rather than react. Responding means there’s clarity and freedom to our engagement with the situation. Reacting, on the other hand, means our habitual patterns are in the driver’s seat, and we may be inadvertently addressing a past situation, not what’s presently unfolding. So, part of determining whether we’re “aligned” to whatever is taking place, and knowing how to engage in conflict if we aren’t, necessitates feeling our feelings with awareness. After all, in charged situations like those that can precede and pervade conflict, strong emotions are often at play. Anger can be especially prevalent. As Lama Rod Owens notes in his (ah-maaaaazing!) book Love & Rage, anger is an energy pattern in our body that arises when we are hurt but don’t yet know what to do about it. But instead of thinking that anger (or other difficult emotions) are a problem, Lama Rod encourages us to let these emotions inform us. We can think, “oh, I’m hella hurt and activated right now,” and then simply feel the feeling. I’m not going to lie: this takes guts. Emotional energy can be strong and uncomfortable. For me, anger is hot, fast-paced, itchy, and quickly coalesces into some kind of molten molasses in my throat. It’s hard to allow it to be, to shape-shift, to stay or not stay, without willing it to go away or trying to transform it into something else. But, that’s the work. (That being said, please take good care if you have a fresh or difficult embodied trauma and make sure to do this awareness work at your own pace. If body awareness ever feels like too much, take a break or try placing your attention on something outside of the body — like a flower, a candle, or the sturdiness of the ground beneath you.)

If you are able to allow difficult feelings to simply be there when you are facing a potential conflict, the reward is this: you’ll gain clarity about what this feeling is, as well as some freedom to be creative in how you respond. Maybe you determine, “oh, I’m just activated and annoyed because this dude’s mannerisms remind me of my insensitive ex-boyfriend, but actually, what he said was harmless.” Or, maybe you realize, “I’m hurt because of the insanity taking place right now and I need to say how I feel so this stops.” When we check-in with how we feel, we commit to our well-being while also giving ourselves a chance to engage in conflict with freedom and space.

So, we’ve dropped into our bodies; we’ve felt what’s going on; and we’ve assessed the situation before us from a place of authentic, embodied clarity. Let’s say we now know that we’re not okay with what’s happening. And so, the first part of our conflict mantra, which acknowledges that we are not aligned with whomever or whatever we encounter, encourages us to respond so that we’re not enabling harm to ourselves or others through silence. Now, the second half of the mantra — “but you still belong” — comes into play. It begs us to infuse the entire conflict with awareness of the other person’s humanity and complexity. For me, without this component, we are responding to violence with violence.

But what does it mean to belong? Belonging is a term I’ve recently fallen in love with — not because it describes a particularly “warm and fuzzy” emotional state, but because it describes the simple, ultimate reality of how things are. I started contemplating the term more intentionally after reading parts of You Belong, an incredibly touching, fresh, and insightful book by author and meditation teacher Sebene Salassie. Though we might experience belonging at some times in our lives and not others, Salassie explains that belonging is, in actual fact, unconditional. It is true whether or not we experience it. Said another way, belonging is not dependent on doing the “right things” or avoiding the “wrong things;” nor is it a specific feeling or thought that we need to sustain (Salassie, pgs 3-4). Rather, belonging is simply the fundamental birthright of all beings by virtue their interdependent existence with everything else. People belong because they are, and they are because everything else also is. As soon as we feel that we or someone else doesn’t belong, we have fallen under the illusion of separateness: mistakenly believing that there could possibly be someone that doesn’t belong in the fabric of reality from which they arose. “Waking up” from the delusion of separateness means coming into awareness of our innate belonging, which is not only the birthright of humans, but all sentient beings. For me, this includes plants, trees, animals, insects, flowers, spirits, ancestors, rivers, and so much more.

And so, we want to engage in conflict with awareness of the belonging of all beings. One way to do this, is to do our best not to objectify one another. Objectification occurs when we over-simplify someone, distilling them down to one “thing.” When we do this, we ignore a person’s history, complexity, multi-dimensionality, and their connection to this interdependent world we’re in. It can happen rather quickly: we get some idea about someone, and suddenly, because we’ve reified that idea, that’s all we can see.

When we distill a person down to one concrete “thing” — we turn them into an object. This gets really dangerous because, as Lama Rod Owens often points out, if someone is an object and not a sentient being, then we feel like we can do all kinds of inhumane things to them. And not only that, when we objectify someone, we deny our own capacity to see complexity. In this way, when we dehumanize someone else, we dehumanize ourselves. Suddenly, not only are we ignorant to the other person’s innate belonging, we are subject to doubting our own.

When I’m completely hardened to someone, and can’t muster any understanding or compassion towards them, I sometimes sit on my meditation cushion and do a “Complexity Contemplation.” This is an exercise (I made up) where I focus on the person I find difficult and imagine their entire life, starting with their birth. Along the way, I think about the following things:

I think about all the joys and challenges they might have experienced as a young infant: how relaxed they must have felt when they were held and rocked, and how hard it must have been when they were neglected or ignored.

I think about what their parents were like, and whether they were able to teach this person the things that might allow them to be vulnerable and trusting. I wonder whether this person had to harden in some ways in order to survive. I think about the wisdom of learning to survive.

I think about all the times they might have been unfairly scolded or otherwise unseen as an adolescent, and all the ways they adapted to cope and fit in as a teenager.

I think about the gifts they developed, the ways in which they expressed and currently express their creativity. I imagine the ways they might be a light in other peoples’ lives without my knowing. I think about whether they have gifts or passions that they are too humble, or too timid to share.

I think about all the ways they endeavor to be good, even if it’s to a plant or animal, knowing that this person too has many moments of unseen compassion and generosity.

I think about how they suffer, and that I too suffer. I think about who might be there for them, and what they might sound like when they really let their guard down. I think about how much they want to be happy and free, and all the ways they express that, and how I too want to be happy and free.

I engage in these contemplations because it brings forth what I’m not seeing when I funnel someone into “just being a jerk,” or “just being selfish,” or “just being ignorant of racial injustice,” any other singular categorization I’m prone to impose on someone. Honestly, without mechanically thinking through such things, sometimes I find it really, really hard to affirm the belonging of certain people. Even with this contemplation, I don’t always succeed. But, it is my commitment to try to see the truth: that this person, difficult as I may find them to be, is not “one thing.” They are dynamic and in relationship with this world, just like me.

In graduate school, whenever I would bring up the universality of belonging as essential to justice work, someone would often pipe up and ask, “So, are you saying that Nazi-sympathizers and KKK members belong?” Yes, but probably not in the conditional way the questioner is implying. It’s not that Nazi-sympathizers and KKK members have a right to see their delusions made manifest, or that they belong by virtue of their delusions. (And, my goodness, they do indeed hold delusions about some people being fundamentally superior to others and what must be done about that…though, we all hold delusions to some degree about this.) No. We can’t and shouldn’t accommodate any platform that seeks to hurt and annihilate others. That would deny the reality of innate belonging. But, if we consider any being, including Nazi sympathizers and KKK members, as somehow separate from us and all there is, or if we don’t see that they too are beings who breathe in and out and who are seeking satisfaction just like us — then we too are guilty of violence. If I stop wishing all beings to be well and free from delusion, then I myself risk being unwell and governed by delusion.

“We’re not aligned, but you still belong” is not a catch-phrase. It’s a practice. These aren’t words we explicitly say while in conflict, they are truths we endeavor to know and embody when conflict is necessary. If our conflict mantra were only: “we’re not aligned;” we’d risk losing perspective, objectifying others, dehumanizing ourselves, and ultimately, causing more harm than good. On the other hand, if our only guide to conflict were: “you belong;” we’d risk denying our own needs, ignoring our own hurt, compromising the safety of others, and condoning systemic violence. Increasingly, in this hyper-polarized world, we need both sides of the phrase. So, put your foot down, but know that you’re ultimately doing it for the person you’re in conflict with, not to destroy them.

Because this mantra is one we practice and embody, it doesn’t give us much help when it comes to figuring out the content of what we communicate in the midst of conflict. I know, in tense situations, it’s often hard to find the right words, especially when initially trying to broach a subject with someone. My experience is that when I am authentically considering another’s complexity, while tending to injustice or the ways I feel hurt — the right words come. Still, sometimes it can be helpful to hear phrases that balance firmness and compassion, to get a sense of what might be possible in the moment. These are but a few of the million-and-one ways that embodying our conflict mantra might emerge through speech:

“You know, what you just said really didn’t land with me. Can you rephrase that or explain what you mean?”

“I love you, but I found what you said really hurtful and enraging.”

“I need things to change so we can move forward together.”

“I’m hoping you might be the one man/white person/straight person/cisgender person I can talk to about the patriarchal/racist/hetero-normative/transphobic harm I’m experiencing. Will you just listen?”

“I’m very concerned that this policy we’re considering contributes to systemic violence. Let’s spend some more time discussing it because I’m confident we can come up with less harmful alternatives.”

But What of Emotional Labor?

It’s true. If you engage in conflict this way, you might be doing way more energetic work than someone who might roll on into an argument as sloppily as can be. This means, you might find yourself in situations where you are doing the bulk of the emotional labor. If you’re not familiar with it, “emotional labor” is a term that describes the taxing quality of fielding and holding another person’s psycho-emotional experience, particularly when they are ignorant of (and actively contributing to) systemic dysfunction that marginalizes you. As Leah Cowan points out in this amazing TED Talk, people in historically marginalized groups are often unfairly expected to do emotional labor for those who are oblivious to their privilege, and this can be incredibly trying. Just know, it’s your right to stop engaging in any conflict when you feel you aren’t be heard or held in return. And remember: silence to self-regulate is LEGIT.

Overtime, however, I’ve realized that part of my commitment to justice, to personal development, and to my bodhisattva vows means that, sometimes, the care with which I approach an interaction is not reciprocated. For me, this is not necessarily a reason not to do it. I have the good fortune of not feeling acutely traumatized at this moment, and so, I can stretch myself a bit. Plus, deep down I know that I too am benefitted from engaging in conflict with an open and bold heart, and that people who can’t reciprocate are where they are. Still, you are entitled to make the call based on how you perceive a conflict and based on your needs. We all have limits and have a right to enforce boundaries. When I experience so much imbalance in the dynamic that I can’t even self-regulate or keep my cool, it’s time to go tend to myself.

Choosing Wisely

I hope it’s become clear throughout this post that conflict can be necessary to deepen relationships we care about, to disrupt the silence that enables harm and abuse, and to foster a more just and equitable world. I also hope it came through that we can engage in conflict boldly and lovingly, in a way that affirms the innate belonging of all. I’d even go so far as to say, it’s not just something we can do — it’s our social responsibility.

When I talk about ethical and social responsibility, I know that it makes some people queasy. In the past, friends of mine have resisted and pushed back, articulating that not everyone is going to be passionate about the same thing. True, true. But social responsibility simply comes with being a social being and living in community; it does not necessarily have to take the form of being an activist. We can be creative with how we carry out that social responsibility based on our talents and context. We can choose where and how we engage our ever-deepening awareness. We can do the work in whatever circles we find ourselves.

Pretty early on, I discovered that my skill-set doesn’t really lie in canvassing or leading marches. I’m not talented at organizing large-scale conferences or acts of disruption (bless those of you who are, and thank you!) But I asked myself,

”Where and how can I be an ally?” I realized that, first and foremost, being an ally meant being honest with myself about the ways in which I am reinforcing systems of harm. For example, if I am constantly capitulating to my feminine conditioning that has taught me, as a woman, to refrain from “ruffling any feathers,” in what ways am I still invested in patriarchy? And if I am not looking at the (embarrassing and saddening) ways I have internalized racism in my mind and body, how am I able to divest from systems of racial violence? No matter what our context, maybe healthy conflict starts by taking a look at the ways in which we are invested in toxic relationships as well as systems of violence.

Doing that internal work is vital. But the next step is actively divesting from harmful systems and relationships, which yes, sometimes necessitates conflict. Here, however, we can be creative! We can choose the contexts where we’ll help based on our passions and heart projects. And so, I engage in healthy truth-telling by sharing my writing, and by speaking with people I’m in relationship with, including my family, friends, and members of my spiritual community. I also plan on being open and transparent with my new chaplain coworkers, when I start a new position in August. Doing this work in community is especially powerful, because I know that others will help keep me accountable — and I thank them for that.

It can be tempting to think that conflict must be geared towards those with the most extreme views (like the KKK.) But, as civil and human rights activist Loretta Ross puts it, “know your sphere of influence.” Sometimes, the good we can do is precisely within the circles we are part of. For example, I have several therapist friends who have brought their ever-growing awareness of whiteness to the work they are doing with their clients. My partner, Dave, has found a way to have kind and productive conflict with friends and sangha members when it comes to racial injustice. These activities are important. We can radiate awareness of innate belonging from where we are, based on our talents and abilities. And we can appreciate our own open, undefended hearts that lie in the center of our activities. Conflict engaged from this place, my dears, can do a lot of good. Shine on.