Delusions of Smallness

How our thinking about our psycho-spiritual "size" impacts our sense of worth...

The bowed-head, melancholic-heart experience of low self-esteem. For weeks leading up to my most recent solitary retreat, it was intermittently palpable. True, I wasn’t walking around thinking of myself as “a piece-of-crap,” or in any other explicitly pejorative sense; but I did feel an acute, uncomfortable uncertainty about “how I was doing in the world.” Insecure might be the right word. I felt small, and not in that “good-and-relieving-cosmic” way, but in that “not-enough” kind-of-way. It was as if a consistent question mark appeared whenever I considered whether my activities, efforts, or even my perspectives were “good.” All the while, what I meant by “good” was vague in my heart and mind. I was falling short of… something. Like it was just out of reach.

I imagine that low self-esteem can have many sources, but I wonder if one of its primary tributaries is the non-recognition of one’s innate goodness. As a chaplain, I encounter a lot of people who use the phrase “low self-esteem” to describe their state, especially after a stroke or an illness has dramatically changed their sense of accomplishment and agency. When I invite them to say more about it, they typically share something like, “I don’t know…I just don’t feel good about myself.” For most of us, even without being hospitalized, that sentiment is oh-so-relatable — we go through periods of not feeling good about ourselves. We feel small in the mirror of our minds, and maybe even embarrassed around others. The question is: what is this goodness we’re hoping to sense about ourselves and where are we looking for it? And, (in keeping with the orientation of this blog,) if we’re really going to heal the split between our dualistic notions of ourselves (as “good” or “bad,” for example) what would encountering a goodness with no opposite look like?

Untangling Yourself from the Past: How Have You Historically Considered Yourself “Good”?

So often, our beliefs about ourselves are inherited and conditioned. We start to have a mental schema of “what constitutes good me” and “what constitutes bad me” even without knowing that we’re subtly categorizing our experience of ourselves. This schema is influenced by how we’re raised; our level of healthy attachment; unexamined habits; and by covert, dysfunctional reward systems embedded in the collective dynamics we’re all swimming in. By pausing and contemplating the historical basis for our self-esteem, we can start to assess whether our framework about ourselves is actually aligned to our present experience.

When I engaged in this type of contemplation, I realized that, in no small part, I tended to measure my own “goodness” by the feedback I was getting from the world. When I looked back at the last 37 years, I saw that, pretty much since birth, I received continual, explicit affirmation of my “progress.” Last year, for example, I was a full-time hospital chaplain in a residency program that provided routine feedback about my work by analyzing recreated written scripts of my visits, providing detailed evaluations, and even eventually encouraging me to stay on as a permanent staff chaplain. Prior to that, I was in graduate school (seminary) for three years and received nearly-constant positive feedback in the form of grades and comments about my coursework. Even as a public interest attorney prior to grad school, I almost always saw the worthiness of my labor: the client won their case; the house was saved; the student loans forgiven; the debt relieved; or the credit reporting agency stopped lying. In kindergarten through college, in law school, and even in the years of working in the policy world between the two: people, grades, accolades, and promotions told me in so many words how I was doing and the reviews were generally encouraging. This might all sound like good news, but by hinging my self-esteem on praise and positive results as declared by the “outside” world, I was giving away a tremendous amount of power. I was also creating a narrow, conditional relationship to healthy self-esteem.

Maybe your historical sense of self-esteem is based on something different. For example, I know I’ve talked to friends who say they tend to feel good about themselves when they’re productive, including when it comes to their personal passions and pastimes outside of the realm of paid work. (Honestly, my self-esteem is often even contingent on how “productive” I am about spiritual studies and practice!) I know others who feel a strong sense of self-esteem when they are in a romantic relationship, or simply in the company of others, but as soon as they are single or alone, feel like their personal stock has plummeted. Still others might base self-esteem on fitness or body image. And, maybe it’s simply an amalgamation of all of these when we really look (in writing them, they’re all so relatable!) But, whether it’s productive = I’m good, not productive = I’m bad; praise = I’m good, no praise = I’m bad; relationship = I’m good; no relationship = I’m bad; fitness = I’m good; flabby = I’m bad, isn’t it exhausting to be incarcerated by unexamined mental mathematics about our self-worth? It’s like we’re dreaming of our own smallness, but haven’t actually woken up to see how the dream compares to reality.

And, of course, there is absolutely nothing wrong with drawing satisfaction or pleasure from productivity, praise, intimacy, fitness, or whatever else tickles you. Experimenting and experiencing is a wonderful thing! It is the placing of these things as the basis for self-worth that I question. When the basis of my self-esteem is something that is bound to come and go, that is — when it is something conditional — its dissolution will likely result in my suffering a sense of lack. Because, after all, sooner or later, I’ll be tired and needing to be still and unproductive; sooner or later I’ll experience the absence of praise or companionship; and sooner or later I’ll be unable to exercise because of an injury, illness, or the simple mechanics of aging. What happens to self-worth then?

The Good News About Low Self-Esteem

All this came to head for me about seven months ago. I moved back to California and had just started a new job as a full-time hospital chaplain. No residency evaluations, no tests, no more hoops to jump through (yay!), and so: no reassurance or praise to be found. My colleagues trusted my competency — it didn’t need to be pointed out. And, unlike law or policy-work, chaplaincy does not lend itself to revealing the fruits of your efforts in unequivocal terms. You accompany others in crisis and you let go. But, this all meant that the feedback loop, which I had previously relied on to feel “good” about myself, was cut. If reassurance about the impact of my work had to some degree watered my sense of self-esteem, I suddenly found myself in a desert.

And yet, the desert’s vastness and austerity is sometimes exactly what is needed to encounter a more fundamental and reliable goodness beyond one that comes and goes. In other words, the moment I experience a reaction of smallness, having been stripped away of what I typically delight and take pleasure in, I am poised to discover a more fundamental experience of being that cannot be stripped away, and that fundamental experience of being is not small in the least. For me, that fundamental, basic sense of being is always there, but it can become “more obvious” when I am denied whatever has historically given me a “high” about myself. It was as if the decor had been stripped and all that was left was the “decorator.” So, though low self-esteem is painful, it’s both pivotal and profound when it leads to a looking at “what’s left.”

Retreat

It’s November, about five months into my new job. The sense of smallness is upon me and I’m half-saddened and half-intrigued by it. I want a strong container to explore it, and I’m realizing that it has been too long since my last solitary retreat. I make arrangements for five days away in a beautiful corner of Northern California, an hour away from home. I prepare my traditional retreat schedule, plan what practices I want to focus on, discuss it all with my teacher, pack my food, and go.

Northern California is a special-kind-of-exquisite in the autumn. The trees are aflame with reds and yellows, and the redwoods seem to have extra dexterity as they’re caressed by the breeze coming over the hills from the Pacific. All I can hear is the swooooooooosh of the wind against the leaves and conifers, the caw of crows, the purr of hustling quail, and the crunch of dead leaves as deer walk by. I’m beyond grateful, and realize the incredible auspiciousness and privilege of being in such a place. I do practices to thank the land and local beings for their generosity; to explain my intentions; and to request assistance and blessings. Then, for the next few days, I sit and practice relaxing into naturalness.

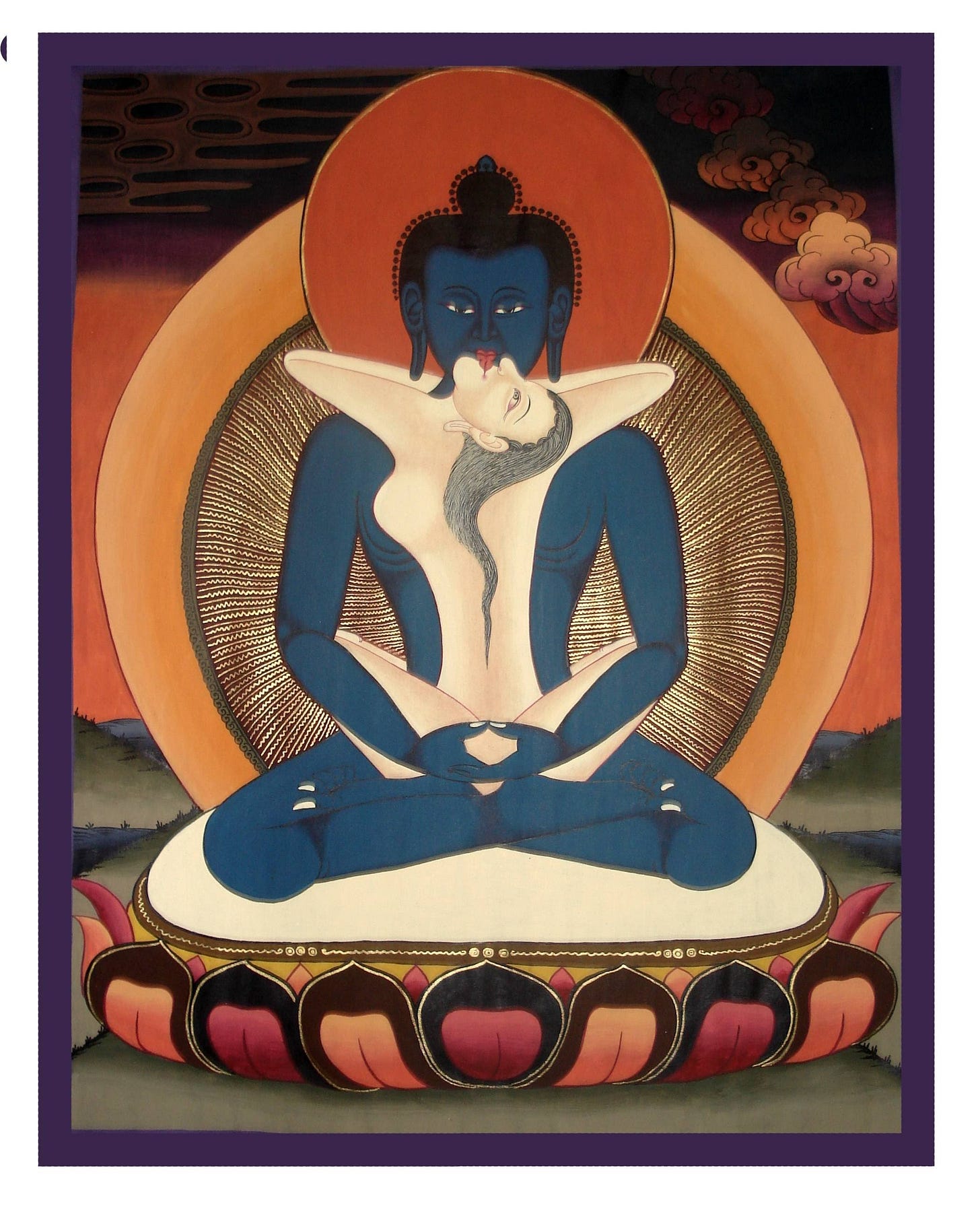

When the mind settles, what I experience is the vastness of awareness, or rather, myself as the vastness of awareness. “Awareness” is not a “thing” because “it” is total openness, extending without center or limit. At the same time, awareness is pregnant with experiences. Thoughts, emotions, mental images, physical sensations, energy movement, and the experiences of sight, hearing, smelling, tasting, and feeling all arise and collapse back into this plane of awareness which, ultimately, none of these phenomena can be distinguished from. Anything that arises, when permitted to express its totality, reveals itself as an unpinnable event in motion, and therefore empty of any singular, independent existence — like fireworks that cannot be captured as they sizzle back into space, or waves that reveal themselves as nothing other than the water they came from. Worries about how “I” am doing, or images of anticipated, future events display like a movie for as long as the mind fixates on them exclusively; only to dissolve easily when the mind, once again, experiences its own empty (free, vapor-like) nature. Even seemingly-solid forms are not as static or separate as habitual thoughts think them to be. When really explored, the sight of my hands in meditation posture, the rim of my eyeglasses, the edge of the sliding door, the tree in the field, the passing deer, all appear in the periphery of my vision as pulsating pixels, like dancing light on water’s surface. They cannot be found outside of awareness. At the level of experience, they are simply images flashing so rapidly that their cohesion is taken for granted. The same is true for the body. Limbs are first experienced as solid, then as earthy heaviness, then as moving sensation, then as energy, until awareness abides in the subtle experience of limbs as unpinnable light-bliss. Mesmerizing. And then, my analyzing mind takes over, trying to catalog everything mentally, and in so doing, imposes that oh-so-familiar dualistic, conceptual lens on the rawness of experience. The solid “I” returns, looking “outward” at experience. But eventually, mind settles once again into its natural state. Once more mind’s essence is seen as the lack of solidity, while the brightness of awareness, mind’s knowing-quality, pervades the entirety of presence. Like a sunlit sky where space and light are inseparable, awareness as a still void and awareness as movement are in union.

This ground of being, the ultimate nature of mind is good. It’s not good because it is isolated from “badness.” Nor is it “good” because it is constructed out of “the right” conditions. Rather, mind is inherently good in that its fundamental nature is openness-to-any-possibility. It is good like space is good, or like the sky is good. Just as the naked sky is pristine and free, but can manifest storms or rainbows, so too mind’s nature is ultimately the goodness of potentiality, whether it manifests high or low self-esteem. It is this radical openness that allows for the experience of praise, or its absence; for the experience of productivity, or its absence; for romantic partnerships, or their absence; and for exercise, or its absence. The inherent spaciousness of reality allows anything to come forth, to express its fullness, and dissolve back into space, including our habits of perceiving and labeling experience as “good” or “bad.” Mind’s ability to experience it’s own insubstantiality (the basic ungraspableness of reality) is good because, at last, stuckness, separateness, and smallness are revealed as illusory and temporary, like insubstantial ghosts on the winds of being, just passing through.

What is self-esteem in the context of this insight? For me, it is resting confidently in the experience that there is no fixed self that could ever be separate from this basic, fluid, beingness. Overtime, I have started to relate to my “self” less as this lanky, well-meaning, dork that you all affectionately call “Malika,” and increasingly as the pervasive, open awareness that this “Malika-event” is backlit and co-constituted by. Paradoxically, self-esteem then becomes knowing that there is no static self to have self-esteem about! And, at the same time, this is only paradoxical from the point of view of conceptual understanding. From the point of view of experiential understanding, there is no paradox.

But, lest you think I’m some kind of adept, let me make it clear that I am a novice at all this and my conditioning to think of myself as a separate, singular being (with an interior world “in here” and an exterior world “out there”) is strong. From the vantage point of this habitual perception, low self-esteem and delusions of smallness take hold because this (seeming) separate self intuits the nonsensicalness of being separate from all there is, and so craves something (seemingly) outside of it to complete it. Usually that means grabbing at my historic source of self-esteem (I’ll take a glass of praise, please!) When that historic source of self-esteem eventually (and inevitably) becomes unavailable, the delusion of smallness dawns, and here we go again, unaware of the transpersonal grandeur of beingness, yet ever-primed to behold it.

On the other hand, from the vantage point of “self” as edgeless, center-less awareness, I’m complete to begin with — or more like, I’m completeness itself. Such completeness inherently has a relationship with the dynamic array of emotional states that arise, with all their ups and downs, because spacious awareness never minds the fireworks that arise and dissipate within it. They arise as awareness, in awareness. Self-esteem here just becomes the knowing of oneself as that completeness, as open inclusivity. It’s amazing that I forget to drop in and simply become what I have always been! But, habits are powerful. They often blind me from “what is.” As they say in the Shangpa Kagyü tradition about mind’s true nature:

So close you can’t see it.

So profound you can’t fathom it.

So simple you can’t believe it.

So good you can’t accept it.

I know there are some that might frown at my talking or writing about my experiences of the ultimate, limited as they may be. And, in one way, they have a point. After all, the Tao te Ching states something like, “those who know don’t speak,” right? But, I suppose I share it because I genuinely don’t think I’m describing anything special or spectacular, only the simple nature of things that is readily discoverable. And, I share it because these simple discoveries have opened my heart. I’m using the language of Buddhism and “mind,” but these are just words, and there are an infinite number of ways to describe our basic, fundamental being. However you call it, is observable in this moment, and nowhere in particular, and wonderful. It is you. It is grand. And it is good.